Opinions of Friday, 29 March 2019

Columnist: Muntaka Chasant

A glimmer of hope comes to Agbogbloshie

The German government through the implementing agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and Ghana’s Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation, has inaugurated a health post and training workshop inside the Agbogbloshie scrapyard.

Dignitaries gathered in this highly polluted place to open a small facility meant to provide Agbogbloshie residents with frontline medical access and help train scrap workers to dismantle electronics safely.

Great idea, except this follows the usual ‘emergency relief’ framework - not exactly addressing the underlying problems - just something to show to donors or taxpayers.

This facility is part of a 25 Million Euros support from Germany to the government of Ghana to address the impact of e-waste.

First, let me get this out of the way - I’m not opposed to the institutional development approach. Not in the sense that post-development theorists such as Arturo Escobar, Majid Mahnema, and Gustavo Esteva have argued about the failures of development in the underdeveloped parts of the world since the years after the second world war.

The post-development school view the post-war development projects by governments and NGOs, which are heavily influenced by development theory (such as the modernization theory), as monolithic, and hegemonic.1

They argue that development projects often end in failures, partly because Governments and NGOs fail to account for cultural variations and local perspectives in their programmes.

They further argue that the practice of development is embedded in a western-dominated discourse, which conceives the underdeveloped parts of the world as inferior.

In short, this thinking demonstrates that western models of development have not worked in the non-western context since 1949.

The post-developmentalists are correct to some extent, I think.

Poor us, don’t we need some pity and money thrown at us at every chance without asking us about the problems, and how it could be solved from our ‘primitive’ point of views?

This argument should not overlook the premises of intervention. There are several cases where intervention has proven successful. The Marshall Plan helped to rebuild Europe after the war.

Did intervention work in Europe because both the United States and Western Europe are part of the Global North?

Back to Agbogbloshie

The most immediate problem at Agbogbloshie is the burning of insulated cables and radial tires to recover copper, radial steel and other precious metals.

The unsafe dismantling of televisions and computers are very serious alright, but this cannot be compared with the air pollution from the burning, which poses immediate health risks to the residents of Accra.

Dr. Stefan Oswald, the Director-General of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Co-operation and Development, mentioned that Agbogbloshie is often sensationalized in the international media.2

“It is not the ‘hell on earth’ like it is often reported in the international media, however, we need to work hard to make it a place where about 10,000 scrap workers can earn a living under improved health and environmental conditions.”

Dr. Oswald is partly correct - Agbogbloshie scrapyard is unlikely the largest e-waste dumpsite in the world, as often reported. There doesn’t appear to be any evidence to support this.

Again, Agbogbloshie is more of an auto dismantling yard than the large e-waste dumpsite you read about in the news.

But he’s certainly wrong about the pollution levels from the scrapyard. "Hell on earth" is certainly not an exaggeration. See video below.

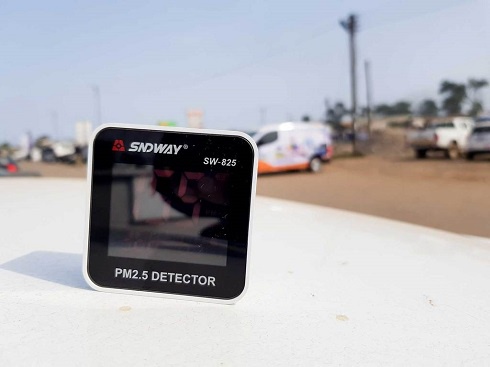

Although burning was brought to a temporary halt to make way for the event, a handheld monitor in my pocket was still beeping from the high particulate pollution (PM) levels inside the scrapyard.

This was while Dr. Oswald was dismissing the international media.

Just outside the scrapyard (in front of Ecobank), my PM2.5 monitor consistently measured more than 150 ug/m3 while the event was ongoing.

You can see a reading in the photo below - 155 micrograms per cubic meter [?g/m3] of ultra-fine particles of 2.5 micrometers or less in diameter which can penetrate and lodge deep inside our lungs.

PM2.5s are linked to heart disease, stroke and lung cancer, and are worse in cities like Accra due to poor air quality controls.

155 ?g/m3 is more than 6 times above the World Health Organization recommended safe limits of 25?g/m3 24-hour mean.

Agbogbloshie is the largest open food market in Accra.

Residents regularly pick up vegetables, fruits, beef and fish here.

Agbogbloshie market attracts people from the hinterland due to low cost of food.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016), one third of street food vendors in Accra pick up their inputs from Agbogbloshie.3

The German Ambassador to Ghana, Mr. Retzlaff, said “this will be a model for e-waste recycling in Ghana”.

Correct, this ‘could’ be a model e-waste recycling facility. But read further below.

There has been a ‘model’ e-waste recycling inside the scrapyard since 2014, and surprisingly, this newly inaugurated facility shares a wall with the Pure Earth and GreenAd 'model’ e-waste recycling facility. More about this below.

Why has the ‘model’ E-waste Recycling Facility inside Agbogbloshie not been successful?

To solve the problem of the burning of insulated wires for copper, Pure Earth, with local partners Green Advocacy Ghana (GreenAd) and the Greater Accra Scrap Association (GASDA) opened an e-waste recycling facility in Agbogbloshie, Accra, in 2014.

This facility was opened with fanfare. A Pure Earth press release on this was titled ’Change and Hope Comes To Agbogbloshie’.

The facility houses wire-stripping machines in shipping containers inside the scrapyard. The machines separate metals from cable plastic coatings.

But there was a problem they did not foresee - the machines could not process the small diameter cables that are commonly burned inside the Agbogbloshie scrapyard for copper recovery.

So the first phase was a failure, which Pure Earth has admitted.

There was a second phase.

They installed new units, this time to help separate the metals from the small diameter plastic coatings.

It’s been about 4 years now, and the burning has gotten worse.

1. They now have a unit that is capable of stripping the small diameter wires alright. But this requires a tremendous amount of time to untangle the wires (like below) before feeding each wire through the granulator and separator.

Open burning takes only a few minutes. So guess which the scrap dealers still prefer?

2. To sustain the facility, scrap dealers have to pay a small token to use the granulator. This is a problem for the scrap dealers. Thus open burning is still their preferred choice.

For now, the wire-stripping machines are only gathering dust.

Another model at this facility is to collect the cables as they were originally collected by scavengers during their daily run around the city, and recycle them in a recycling facility elsewhere.

The scrap dealers lose about a dollar per kilo of copper cables this way. This is too much money to let go for selling the cables as they were scavenged, so this option again is not favorable for them.

They prefer to burn them, to make a little extra.

Despite spending nearly $150,000, this ‘recycling’ model has not solved the burning of insulated copper wires for copper recovery at the Agbogbloshie scrapyard.

Most of the scrap workers live in this settlement.

A study in 2008 found scrap-related work as the second category of employment in this slum.4

Twenty more million Euros are in play here. Some for the yet-to commence e-waste recycling facility at Agbogbloshie.

I have asked about 30 burners (most of the faces of Agbogbloshie you see on the internet), and they are not aware of any impending e-waste recycling facility.

How could anyone attempt to solve something as complex as Agbogbloshie without involving the people directly?

Local involvement does not imply the Minister and his henchmen.

As a matter of fact, you may have to distance yourself from the government in order to earn local trust in certain parts of the developing world (Arce and Long, 1993).

Entertainment