Opinions of Tuesday, 31 December 2019

Columnist: Pippa Stevens, CNBC

The battery decade: How energy storage could revolutionize industries in the next 10 years

What a difference a decade can make. In 2010, batteries powered our phones and computers. By the end of the decade, they are starting to power our cars and houses too.

Over the last ten years, a surge in lithium-ion battery production drove down prices to the point that — for the first time in history — electric vehicles became commercially viable from the standpoint of both cost and performance. The next step, and what will define the next decade, is utility-scale storage.

As the immediacy of the climate crisis becomes ever more apparent, batteries hold the key to transitioning to a renewable-fueled world. Solar and wind are playing a greater role in power generation, but without effective energy storage techniques, natural gas and coal are needed for times when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t howling. And so large scale storage is instrumental if society is to shift away from a world dependent on fossil-fuel.

UBS estimates that over the next decade energy storage costs will fall between 66% and 80%, and that the market will grow to as much as $426 billion worldwide.

Along the way entire ecosystems will grow and develop to support a new age of battery-powered electricity, and the effects will be felt throughout society.

Changing electrical grid.

If electric vehicles grow faster than expected, peak oil demand could be reached sooner than expected, for instance, while more green-generated power will alter the makeup of the electricity grid.

In a recent note to clients, Cowen analysts said that the grid will “see more changes over the next ten years than it has in the prior 100.”

The growing energy storage market offers no shortage of investing opportunities, especially as government subsidies and regulations assist the move towards clean energy.

But like other highly competitive markets — such as the semiconductor space in the 1990s — the battery space hasn’t always provided the best return for investors. A number of battery companies have gone bankrupt, underlining the fact that a society-altering product might not reward shareholders.

“Eventually this will come down to some industry leaders who make some money,” JMP Securities’ Joe Osha said. “I think all these companies are going to do a good job of delivering declining prices for [electric vehicle] manufacturers over the course of the next 5-10 years. I am not so sure that they are going to generate great stockholder returns in the process.”

That said, while it might be tricky to invest in pure-play battery companies, there are opportunities to target companies that stand to benefit from the shift to a low-carbon world.

For example, Sunrun is the largest residential solar company in the United States, while NextEra Energy is one of the country’s largest renewable power companies and is currently building out its utility-scale storage.

As scientists alter the chemical makeup of batteries and companies make bets on what could be the next breakthrough technology, Dan Goldman, founder at clean tech-focused venture capital firm Clean Energy Ventures, said that areas like innovative battery management systems are a good bet for investors since they can work with any battery technology.

“Capturing the massive economic opportunity underlying the shift to controls and battery-based energy systems” requires that not only planners, policymakers and regulators but investors “take an ecosystem approach to developing these markets,” researchers from Rocky Mountain Institute wrote in Breakthrough Batteries: Powering the Era of Clean Electrification.

Batteries: the new star of science

Battery technology in its simplest form dates back more than two centuries. The word itself is an umbrella term since batteries come in all shapes and sizes: lead-acid, nickel-iron, nickel-cadmium, nickel-metal hydride, etc.

Lithium-ion batteries — which itself can be a catchall term — were first developed in the 1970s, and first commercialized by Sony in 1991 for the company’s handheld video recorder. They’re now found in everything from iPhones to medical devices to planes to the international space station.

Perhaps the greatest indication of the role these batteries have played in modern society is that this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to the three scientists who developed the lithium-ion battery.

“Over the past decades, this development [lithium-ion batteries] has progressed rapidly, and we can expect many more important discoveries to come in battery technology,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said in October. “These future breakthroughs will undoubtedly lead to further improvements in our lives, not only for our convenience, but also with respect to global and local environments and, ultimately, the sustainability of our entire planet.”

Electric vehicles: going the distance

Tesla was the first car company to commercialize a battery-powered electric vehicle when it unveiled the Roadster in 2008. Automakers had previously tinkered with hybrid models, but they were generally uninterested in fully electric cars, given the high cost of production.

But consumer tastes have shifted over the last decade, and as regulatory oversight increases — especially in Europe — automakers have had to keep up.

Virtually all automakers now offer or plan to offer fully electric — or, at the very least — hybrid car models.

In November Ford unveiled its all-electric Mustang Mach-E, which is part of the company’s $11 billion plan to develop 40 all-electric and hybrid models by 2022, and in March Volkswagen increased its electric vehicle goal to 70 new models by 2028, up from a prior target of 50.

Battery pack prices for electric vehicles are typically looked at in cost per kilowatt hour. Over the last ten years prices have fallen as production has reached economy of scale.

They now cost around $156 per kilowatt-hour, according to BloombergNEF, which is an 85% decline from 2010?s $1,100 plus/kWh cost. And continued production and improving efficiencies are set to make prices drop below the $100/kWh price by 2024, BloombergNEF found, which is significant since that’s the industry consensus for when electric vehicles will reach price parity with internal combustion engine vehicles.

“Although the concept of electric vehicles is not new, what is different in this automotive cycle is the availability of reliable and low-cost batteries that possess excellent energy and power capabilities in a practical form factor,” Cowen analyst Jeffrey Osborne said in a recent note to clients.

Worldwide sales of plug-in electric vehicles — which includes battery-powered electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles — hit 1.98 million in 2018, according to the International Energy Agency, bringing the total number of electric vehicles on the road to more than 5.1 million.

That’s still a very small portion of the 1 billion-plus cars on the road today, but the number is expected to keep growing. BloombergNEF predicts that by 2040 57% of new passenger car sales will be electric, which would bring the total electric fleet to 30%.

Tesla is currently the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, and while it has yet to turn a profit on an annual basis, it has posted a profit on a quarterly basis, including in the most recent quarter. The company has proved to be somewhat polarizing from an investing angle, given the frequent delivery target misses and the sometimes erratic behavior of CEO Elon Musk.

But the company has been successful in getting the price of its battery pack down. This is in part due to Tesla’s gigafactory in Sparks, Nevada which operates close to peak efficiency, and also because the company’s residential and utility storage options help to spread the fixed costs of battery production. The company has also benefited from government subsidies and streamlined operations at its gigafactory.

The battery is the key differentiator between electric vehicles, since the car’s range is determined by the amount of stored energy, and it also determines how long the vehicle takes to charge.

In a recent note Credit Suisse said that it’s important to give “credit where due” to Tesla over the company’s battery development. The firm has an underperform rating on the stock, but said that the automaker has an “edge over other automakers in electrification” thanks to the energy density of its battery, among other things.

Tesla’s compact Model 3 starts at $39,990 — not including savings from government subsidies and gas — meaning that it’s still significantly more expensive than gas-powered compact vehicles. Another issue that automakers will have to tackle going forward is longer range on a single charge and faster charging times, both of which stand in the way of widespread adoption.

But with battery costs coming down, S&P Global Platts said electric vehicles could become competitive in places with high oil prices as soon as the next two to three years.

“Tesla brought a brand to market, and it really helped the whole industry,” said Austin Devaney, IHS Markit director of global inorganics. “You’ll get to where the pocketbook side will start bringing more people into the fold for electric vehicles, so you’ll see an increase in penetration rates over the coming years.”

Investment opportunities in the battery supply chain

The primary reason battery-powered electric vehicles are still relatively expensive is the cost of the raw materials required in their production. In addition to lithium, other minerals like cobalt and graphite are needed for lithium-ion batteries, as well as metals like nickel, aluminum and manganese.

Electric vehicles now outpace consumer electronics in the demand for lithium. While there’s a growing demand for the mineral, prices have plummeted in the last decade after a ramp-up in production outpaced slower-than-expected sales of electric vehicles, S&P Global Platts said. The firm said that it expects demand from transportation and power sectors to nearly triple over the next five years, and that as “momentum builds, demand could outweigh supply.”

Chemical company Albemarle could be one of the beneficiaries of increasing demand since it has lithium sites around the world, including in Silver Peak, Nevada and Salar de Atacama, Chile. The stock has struggled over the past few years, and in the last year the number of Wall Street analysts that have a buy-equivalent rating on the stock has fallen from 80% to 52%.

But not everyone has given up on the stock. Jefferies analyst Laurence Alexander said in December that it’s “one of the most intriguing 3-5 year stories.” His $83 target is 15% higher than where the stock currently trades.

Other lithium extractors include Philadelphia-based Livent, which was spun out of FMC Corporation, and Chilean company Sociedad Quimica y Minera De Chile S.A.

When it comes to actually making battery cells for the battery pack, the market is dominated by Asian companies like Panasonic, CATL, LG Chem and China-based BYD, which is nearly 25% owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

Panasonic has a partnership with Tesla, and LG Chem makes batteries for General Motors and Ford, among others.

In December GM and LG Chem announced that they will invest up to $2.3 billion by 2023 to form a joint venture in Ohio for production of battery cells for electric vehicles. “The new facility will help us scale production and dramatically enhance EV profitability and affordability,” GM CEO and Chairman Mary Barra said at a media event announcing the new factory.

Devaney said that we’ve reached a “tipping point” of sorts, where material players can see the parity in battery cell and pack prices. “Five years ago… electric vehicles were more of a novelty … the consumer didn’t necessarily pick up on the benefits, today they are.”

Powering your phone to powering your home

Demand for bigger and better batteries to power electric vehicles has had a ripple effect, including into the home energy storage space. This is especially true as falling solar prices, coupled with government subsidies, have encouraged consumers to switch to renewable sources of power.

In a November note to clients JMP’s Osha said that SunRun, which offers solar and storage options, looks poised for an “excellent 2020,” in part because of the growth potential from the company’s storage business.

“The uptake of storage is notable both at RUN and across the industry – residential batteries have gone from being a curiosity to an increasingly common part of a new residential solar installation,” he said.

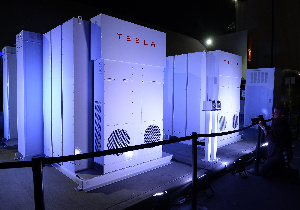

Tesla is another company that offers solar and storage with its Powerwall battery, which Baird analyst Ben Kallo said is currently an “undervalued” part of the company, but one that he expects to become “a larger area of focus as margins expand and deployments grow.”

While both of those companies also offer solar installation, other companies, like Enphase Energy, offer batteries that integrate with existing solar systems. Enphase is the top performing stock in the NASDAQ Composite this year, after soaring 465%.

The next step: utility-scale storage

The biggest potential market for energy storage is not individual consumers, however, but massive utility companies.

Renewables like wind and solar are providing more and more power for the grid. But until effective energy storage is developed these intermittent sources will continue to rely on fossil fuels.

Put simply, the way the electric grid typically operates at present is that power used is generated just moments before. There’s not a lot of inventory, so supply and demand must be in balance at all times.

But as battery prices fall, more and more utility companies are integrating lithium-ion batteries into their systems. At the moment, they’re primarily used to replace what’s known as peaker plants — plants typically powered by natural gas that are only used at times of peak demand. They’re also beginning to replace diesel generators in places that have continuous power requirements, such as hospitals.

Government incentives and falling solar and wind costs are also accelerating the viability of energy storage.

“10 years ago batteries were aspirational as far as a solution to a higher penetration of renewable energy in the electric grid, and today I think you can see a line of sight over the next 10 years to that aspiration becoming a reality,” Ultra Capital managing director Kristian Hanelt said to CNBC. He added that utility companies have a natural advantage since they understand the transmission grid, and know where they can benefit.

NextEra Energy is among the country’s largest renewable energy providers, which includes energy storage offerings. In a recent note to clients Credit Suisse called it one of their top investment ideas, based on NextEra’s “heavy exposure to the fast-growing renewables industry” and “world-leading large-scale renewable development business.”

Other names offering energy storage include Pennsylvania-based EnerSys, as well as Pinnacle West Capital Corporation, which in February announced plans to add 850 megawatts of battery storage in Arizona over the next 5 years.

Currently, the largest lithium ion battery installation is located in South Australia and powered by Tesla. It has 100 megawatt capacity, which, according to the site, allows it to power 30,000 homes when dispatching at peak output. In November France-based Neoen, which operates the site, announced a 50% expansions which will raise capacity to 150MW.

Renewable energy equipment makers and operators, as well as chemical and materials companies could also benefit if storage makes wind and solar power more feasible. Osborne noted that new software will be required to help utility companies understand power needs as renewables and electric vehicles draw from the grid.

“We see the implementation of intelligence across the electric grid as one of the next big waves of IT spending and an emerging investment theme that will likely play out over the next 10-20 years. Fundamentally, the Smart Grid is a large-scale software integration exercise leveraging communication sensors across the network,” he said.

The next decade

Costs that remain high are among the reasons preventing a surge in lithium-ion battery grid integration. Another factor is that this specific type of battery may not necessarily prove to be the best suited to storing energy for longer periods of time. They’ve also been known to catch fire, and there are issues with some of the required components like cobalt, almost half of which comes from Congo. Recycling and the environmental impact of metals extraction are other issues to watch.

Billions of dollars are being spent to find alternatives. Solid-state batteries — which use sodium, for example, instead of liquid electrolytes — is one possible option, as are flow batteries, which use tanks of electrolytes to store energy. But neither of these are viable options just yet.

While the exact type of battery that will win out is unknown, what’s certain is that batteries will play an even larger role in powering our lives going forward.

“Massive investments in battery manufacturing and steady advances in technology have set in motion a seismic shift in how we will power our lives and organize energy systems as early as 2030,” researchers from Rocky Mountain Institute wrote in Breakthrough Batteries: Powering the Era of Clean Electrification.

Entertainment